Thibodeaux: Boudreaux, did you get the parrot I sent you for your birthday?

Boudreaux: Yes, it was good!

Thibodeaux: You ate the bird?! That bird spoke five different languages!

Boudreaux: Then he should have said something.

(An original by Ronald Fonseca)

We have heard them, but have you ever stopped and wondered where these "Cajun" jokes started? I, for one, recently asked this question. In this newsletter, I will take a quick look into the history of humor in Cajun culture, its influential figures, and the critical events that shaped the relationship between Cajuns and their humor.

Acadian Exile from Nova Scotia - Post-Civil War (Reconstruction)

When I first started researching this topic, I thought the connection between Cajuns and humor began in the 20th century. However, the more I read, the more I realized that I had to look back to the beginning of the Cajun story.

Cajuns are descendants of Acadiens, French Catholics who lived in Nova Scotia. In 1763 England gained control of Canada and made several unsuccessful attempts to force the Acadiens to swear allegiance to the Crown of England. Eventually, the English expelled the Acadiens from Nova Scotia. It took a decade for them to settle in what is now Southwest Louisiana (Acadiana). "During the Cajun's exile, to further their cause, the English began to paint the Acadiens as sinners" (Richardson 89). When the Cajuns settled in Louisiana, they chose an isolated area that was cut off from the outside world until the 20th century and the creation of the interstate system. Being insulated from the rest of America made the Cajuns mysterious and gave them an allure in the eyes of non-Cajuns.

Following the US Civil War, the American Anglo-Saxon world began to become acquainted with the Cajun culture. During this time, satirists moved to New Orleans. They frequently used Creole/Cajun accents to protest the political scene in New Orleans. For example, a comedian named John McLoughlin created the first Creole/Cajun character as his "mouthpiece" (Deborah Richardson 103). This character was named Jack Lafaience. Being from somewhere other than New Orleans or Louisiana, these satirists would constantly confuse Creole accents and Cajun accents. Richardson has gone on to posit that "… the Cajun dialect humor in Louisiana had its foundations in the literary movement that followed the Civil War [and was also]…spurred by a growing hunger for the exotic by readers in New England." According to Richardson, the exposure of "Anglo-Saxons" to the Cajuns that began after the Civil War and Reconstruction did not actually bring Cajuns to the nation's limelight, but it did begin to bring about an awareness to the rest of the country of places in Louisiana outside of New Orleans.

This led to an eventual national appreciation of Acadiens and their humor.

Early 20th Century

Following the turn of the Twentieth Century, a homegrown satirist named Walter Coquille began to use the Cajun accent to poke fun at corrupt politicians, especially Huey P. Long. The character Walter Coquille created was Telesfore Boudreaux, the Mayor of Bayou Pom Pom. The Mayor of Bayou Pom Pom made such a splash that he even got Long's attention. "The Mayor of Bayou Pom Pom is the only guy who ever defied me and got away with it. If I ever find that little crawfish village of Pom Pom, I'm going to impeach the mayor!" (Richardson 110). This Boudreaux was different from the modern-day Boudreaux we all love. Coquille aimed to tarnish and harm Long's reputation in any way possible, and he did so by making fun of Long. According to Richardson, the style of humor that Coquille curated is known as the "old" style of comedy. It used stereotypical accents, poking fun at the lack of education by using poor grammar and misspelling words. The "old" style of humor would stay popular and give us characters such as Mrs. Telesford Boudreaux and Claude and Marie, all of whom would use stereotypes to amuse and appease the upper-echelon crowd.

Cajun Renaissance to Modern Day

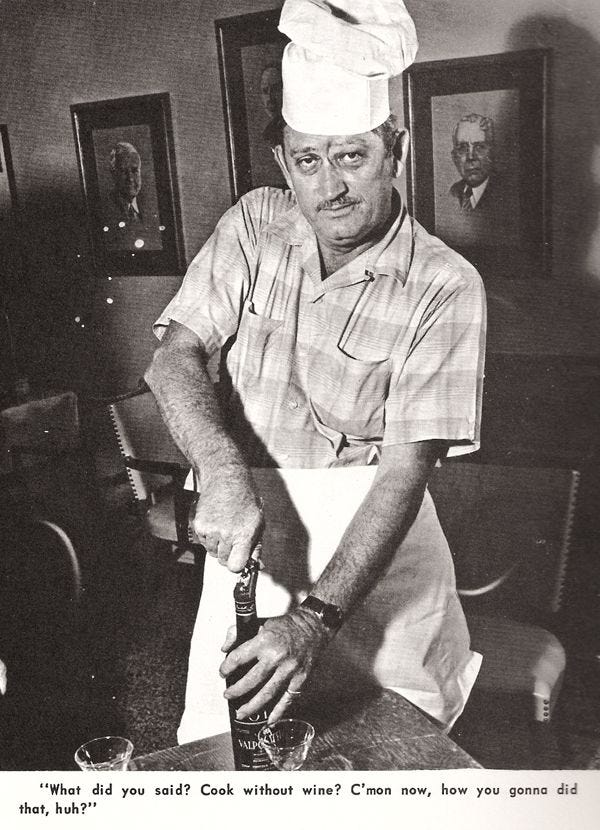

Starting in the 1960s and until the present day, the "Cajun Renaissance" has taken place. During this time in Cajun history, the Cajuns began to promote their culture in their own way. It was also during this time that Cajun culture began to be recognized nationally. In 1968, a prominent lawyer and past Congressman, James Domengeaux, helped pass a law that established CODOFIL (Council for the Development of French in Louisiana), preserving, developing, and promoting Louisiana French (Cajuns) and Creole culture and heritage. We began to see characters like Bud Fletcher and Justin Wilson emerge. Bud Fletcher was born and raised in Jennings, Louisiana, and "was the first humorist not to use malapropisms" (Richardson 115). Fletcher created Cyprienne Robespierre, an authentic Cajun character that would be the end of the "old" style of Cajun humor. We all know Justin Wilson, the famous chef on TV whose iconic red suspenders helped him bring Cajun culture to TV. He leaned into Cajun stereotypes but was the first internationally recognized Cajun character.

The "Renaissance" was also the time that the federal courts got involved. The US District Court located in "Cajun Country" made a ruling that was a huge win for "Cajun Culture." In 1980, in Roach v. Dresser, the federal court recognized the Cajuns as a national ethnic minority. This recognition confirmed the value of the Cajun Culture. We began to see a turning point in the history of Cajun humor. In March 1988, the first International Cajun Joke Telling Contest was held in Opelousas, Louisiana. This contest was an official turning of the tide in how Cajuns used humor in their favor. "That night marked, in a clear and definite fashion, the division between the "old" brand of Cajun dialect humor and the "new" brand" (Richardson 2).

Since the 1980s, Boudreaux and Thibodeaux have continued to be popular. It is true that, at times, they poke fun at Cajuns. But now we see people creating their versions of jokes where Boudreaux and Thibodeaux are sharp-witted, outsmarting their competitors.

"Boudreaux was sitting in the City Bar in Maurice, La. one Saturday night, and had several beers under his belt. After a while, he looked at the guy sitting next to him and asked him,

'Hey, you wanna hear a good Aggie joke?'

The big guy replied, 'Let me tell you something: I'm an oilfield roughneck, I weigh 270 pounds, and I don't like Cajuns. My buddy here is a pro football player who weighs 300 pounds, and he doesn't like Cajuns either. His friend, on the other side, is a professional wrestler, weighs 320 pounds, always has a chip on his shoulder, and likes Cajuns even less than we do, and we are all Aggies. Do you really want to tell us an Aggie joke?'

Boudreaux, all 150 pounds of Cajun attitude, told him, 'Well, I guess not. After all, I don't want to have to explain it three times!'" (Richardson 1).

Now that Cajuns have regained control of their humor, we see the likes of Jourdan Thibodeaux, who uses humor as a way to spread Cajun culture - an excellent way to bring Cajun culture, Cajun French, and the preservation of Cajun history to modern times.

Richardson, Deborah R. Performing Louisiana: The History of Cajun Dialect Humor and Its Impact on the Cajun Cultural Identity. 2004. Louisiana State University, Doctoral Dissertation.

Interesting read! I'm a Cajun girl from Eunice, now living in Baton Rouge. The older I get, the more fascinated I am by our culture! I'm also a writer (frustrated at the moment) who aspires to use her words to revive some of our traditions. I just wanted to introduce myself and say, "Thank you for what you do!" I miss the days when everyone around me spoke Cajun French, so I find myself clinging to every little piece of our culture and history I can find. It's not quite the same as listening to Maman and Tataunte speak the language, but it helps!